The Screenwriter’s Life and the Hero’s Journey

May 30,2018

Among the many aspiring film-makers who describe themselves as screenwriters, or more vaguely, simply pitch the film script or scripts they've written with the firm conviction that the spontaneous outpouring they have written is great, only a minority have truly applied the craft of screenwriting as a lifestyle and pure discipline in its own right, and of those, an even tinier minority achieve acclaim and financial reward as professional screenwriters. The statistic sometimes quoted (and there is no definitive single source) is that only 3% of those who write screenplays can have a paid and sustainable career, and as I have also heard this figure applied to composers, it would be interesting to know whether novelists, visual artists, designers and inventors are working against similar odds, while for actors an enduring, respectably paid career succeeds for just one in many thousands. For women breaking into the film industry as a whole, we can probably cut the odds by at least a further 1:10, although this may be about to change as a consequence of sexual assault scandals, the “Me Too” Campaign and a truly diverse Academy Awards this year.

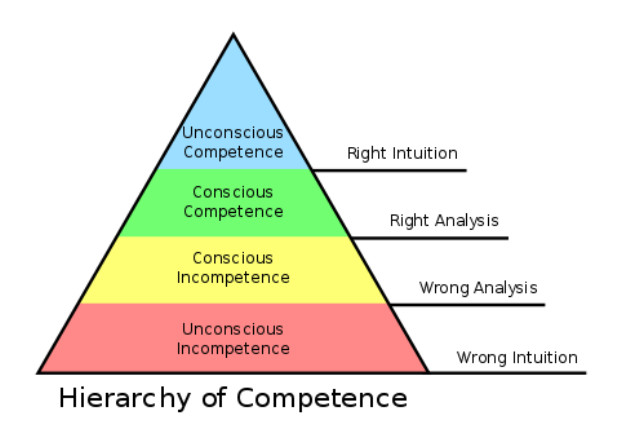

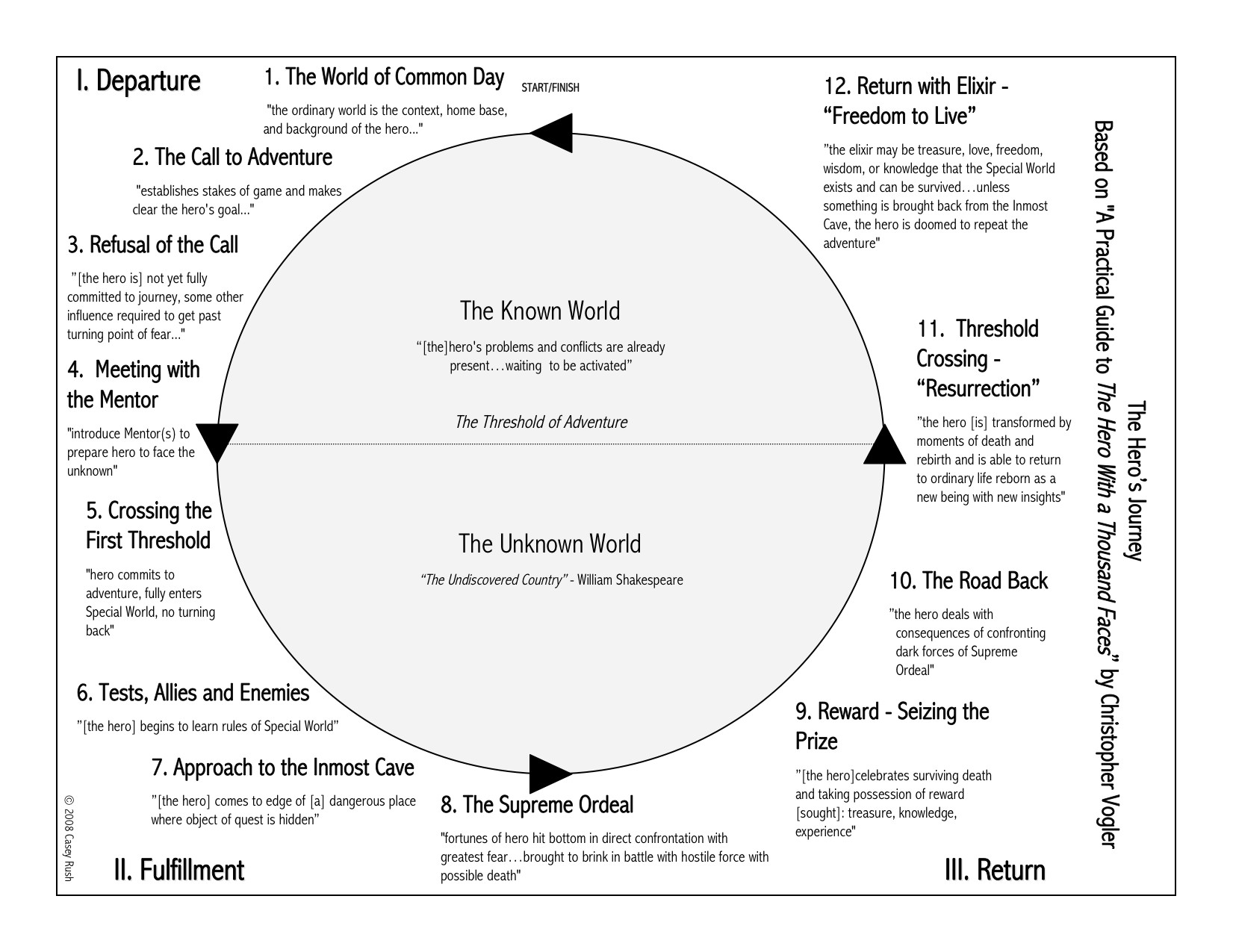

Consider all areas of the creative industries where “true” artists must not only conceive the original ideas and content that can attract an audience on a large scale, but must also demonstrate the resilience, receptivity and adaptability to engage in a prolonged process of development, comparable to the archetypical “Hero’s Journey”. In reality it is extremely rare to experience a single quantum leap, or an “overnight success”. The flow state of a successful and talented creative is based on all of the learning from mistakes made and insights gained over time, and this commonly used psychological model of Hierarchical Competence is a simple starting point that best applies to the acquisition of more linear skill sets (such as learning to drive). Even this most simplistic application to learning is a test of will when tempted to turn back at the threshold between the familiar and the unknown, because fear and avoidance are part of the "incompetance" that motivates learning.

Many screenwriters who have studied their craft over some years and acquired a library of relevant works, will have read and used The Writer’s Journey, Mythic Structure for Writers, by Christopher Vogler, a set of story template tools which map the processes of personal development interactively with the external world. It resonates as an accurate tool for finding thematic meaning in the trials of the human condition, and for the screenwriter using these tools, I recommend considering how these story archetypes apply to their own personal creative journey. The earlier work “The Hero with a Thousand Faces”, by Joseph Campbell is considered to be the seminal source on the subject, drawing on numerous examples of Greek mythology, but Vogler’s book is by far more accessible and applicable to writing for film.

It is worth asking yourself as a screenwriter whether your desire to write has been a true call to action that simply won’t go away. Has it changed your everyday world and re-defined you in ways beyond anything you could have originally imagined? Perhaps it helps to understand that the guardians of the first threshold take a variety of forms: the allies who support in the form of family, peer group or friends, as opposed to the deceptively appealing ally-opponents who seem helpful at first, but are easily distracted, or even actively delay your progress with enticing promises that they cannot or will not keep. True mentors may seem to be opponents, when in reality they are using their seasoned industry experience to alert you to the sheer level of knowledge required, testing to see whether you really have the humility to learn (a quality that is quite different to low self-esteem or false modesty), and tenacity to see through the journey to completion.

Further along the screenwriter’s journey, the approach to the innermost cave can be the point at which all sense of purpose has been lost: skills have been honed and sacrifices made, such as the long hours in solitude required to write and re-write quality scripts, often with considerable financial, social and emotional costs. The lifestyle requirements of a dedicated writer may continue to burn through personal resources without yielding substantial results, leading to the supreme ordeal, often coupled with the “dark night of the soul”, a low point that demands an in-depth personal audit, not only of one’s own capabilities and professionalism, but of the entire foundation upon which one’s existence is built.

Screenwriting Guru Robert McKee refers to the tension created by the repeated gap between expectation and result, here in the context of the story beats that require the protagonist to take escalating action, but bridging this gap in true life is a parallel conundrum that screenwriters and producers have to address repeatedly with ever more inventive and wily strategies: refining pitches, rotating projects, re-visiting old contacts with fresh updates, finding new funding streams, researching technologies and cross media platforms to give a few examples.

In Cannes I was talking with a well credited US feature producer who stated that the main job the writer must do is focus on is to write a story that jumps off the page, and from that the development from script to screen will naturally follow. So true, and so elusive to measure by the writer’s own subjective judgement, when an industry ready script by default has usually been through countless rejections and revisions, either by incidental (and sometimes scathing) feedback that forcefully re-invents the writer’s perspective, or through re-writes done in response to professional coverage when the near industry ready script is found to be either too close in content to an existing film, too controversial in the light of a new social or political paradigm, or too over-written and in need of de-cluttering to re-define its central premise and theme. We discussed the difference between the training of British and American screenwriters, and that US counterparts usually have to write 4-5 scripts before they graduate with a Degree in Screenwriting, compared to 1-2 scripts in the UK.

Talent agents and managers usually prefer to sign a writer who has written several scripts, while another measure of a writer’s accomplishment is having written continuously for five years or more. If one applies the principle that it takes 10,000 hours or more to embed a set of skills to a high professional level, then a screenwriter would need to write the equivalent hours of a full time job over seven years to be the professional equal of a doctor, architect or other highly specialised professional, bearing in mind that we are creating a blueprint (script) for a product (the film), that will cost from hundreds of thousands to millions to make, with considerable risk of financial loss if the story has not been adequately developed, and all of the requisite market intelligence used to assess how the film can most effectively be made and consumed. Yet we screenwriters are so desperately keen to fast-track this process, often forming hasty collaborations with repeatedly stalling and frustrating results.

However, by embracing the screenwriter’s life as a heroic journey, these setbacks and tests become less about the fleeting perception of professional milestones being met, and more about the insight that success is defined not just by the quality of the stories one writes, but the holographic and cyclical ways in which personal story and fiction begin to infuse each other: life infusing art, and art infusing life. Metamorphosis on a scale that asks for everything the artist can both give and receive: a series of tests, ordeals, resurrections, re-inventions, defeats, and most surprisingly, the resulting commitment to a heightened awareness beyond creative striving, beyond any accolades, that brings right analysis and right intuition together to bear on the previously unsolved puzzle of script to film development. This in itself is the ultimate prize from which results accrue and any artistic recognition grows and endures.

The Wizard of Oz has been used as an example film by Christopher Vogler in that its main characters pass through the various stages of the hero's journey. In this scene, the Cowardly Lion is given his medal (the reward) for courage.

Written by Sina Bowyer